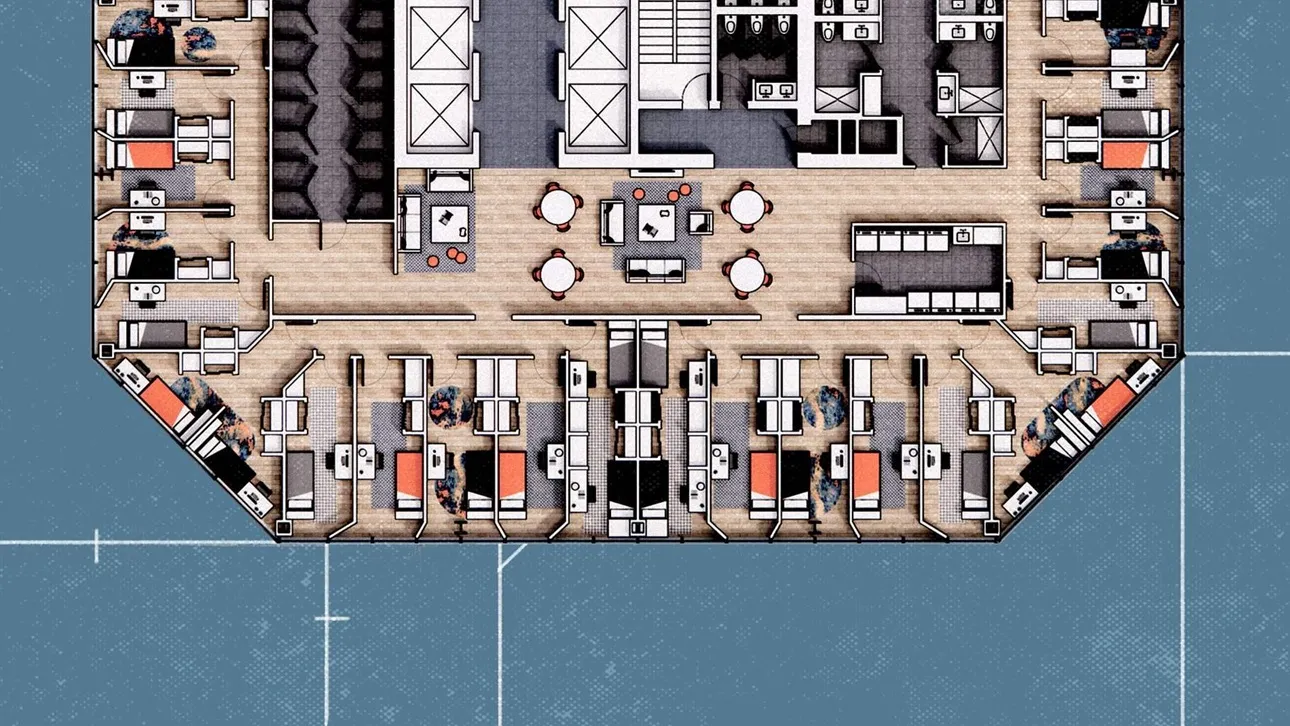

Researchers have proposed yet another way for cities to use the glut of office buildings left vacant amid the shift to remote and hybrid work: Turn them into dorm-style, co-living residences with private sleeping areas and communal kitchens, bathrooms, living rooms and laundry facilities for each floor.

“This is a real opportunity for downtown revitalization and to replenish the low-cost housing stock” relatively quickly, said Alex Horowitz, The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative project director, on a Monday webinar. The webinar highlighted the findings of a report released today by Pew and Gensler, a global architecture, design and planning firm, on the potential of converting offices to co-living spaces.

The concept of office-to-residential conversions drummed up significant enthusiasm among city leaders as it became clear that remote and hybrid work is here to stay. However, it has become clear that what seemed to be a simple idea is hindered by challenges including office layouts that are not easily translated to legal apartments and restrictive zoning policies.

The Pew and Gensler researchers say co-living is a way to skirt some hurdles. The construction cost of converting an office to a co-living design is roughly 25% to 35% cheaper than converting to traditional apartments, Horowitz writes in a report analysis co-authored by Tushar Kansal, senior officer of Pew’s housing policy initiative. That’s in part because developers can keep plumbing and kitchens in the center of each floor, where they typically already are in offices. With narrow, deep “microapartments,” each floor could accommodate about three times more units than a traditional apartment building, the researchers say.

The result of cutting costs while maximizing units? Lower rents for tenants and a greater return on investment for cities looking to subsidize affordable housing, according to the researchers. “For the same levels of subsidy, cities could get many more low-cost homes than they're getting today,” Horowitz said.

The report analyzes the feasibility of co-living conversions in three cities: Denver, Minneapolis and Seattle. In Denver, for example, the $300,000 subsidy needed to build a studio apartment affordable to someone making 35% of the area median income could support the creation of 13 co-living units in a converted office building, according to a press release about the report.

Who would live in these buildings? The researchers envision co-living being a good fit for students, young professionals, retirees, veterans, people who have recently moved to a city and workers in the service industry. Institutions could lease entire floors for specific purposes. For example, a university could rent a floor for student housing or a city could use a floor for supportive housing for residents who formerly experienced homelessness. The model could even proactively reduce homelessness, Horowitz said on the webinar. “Adding a new lower rung on the housing ladder will necessarily reduce inflows into homelessness by improving affordability,” he said.

It’s not necessarily an ideal housing type for families, Horowitz conceded. “This isn't solving every problem out there in terms of housing,” he said on the webinar. “But we know the most undersupplied type of housing are smaller, well-located homes aimed at one- and two- person households.”

Horowitz said on the webinar that he is not aware of any large office buildings in the U.S. currently being converted into co-living spaces as the researchers imagine. “This is new,” he said. “This is still conceptual.”

Swapping out office chairs and desks for microapartments has its challenges. These conversions are likely infeasible without some sort of financial support, such as “an investor comfortable with a modest rate of return, a somewhat below-market rate loan, a subsidy from a city or philanthropy, or a building that can receive a historic tax credit,” Horowitz and Kansal write in an analysis of the report findings. “The anticipated rate of return would not be high enough to attract capital from private equity or similar investors if none of these conditions are met,” they say.

Plus, the regulatory landscape in many U.S. cities preempts these conversions from happening in the first place, Horowitz explained on the webinar. Some cities simply don’t allow co-living where residents share bathrooms and kitchens, and others block residential units in areas zoned strictly for commercial use, he said. Jurisdictions may also mandate minimum unit sizes or operable windows, making the researchers’ co-living designs infeasible. Another major blockade is parking minimums, Horowitz said.

“Enabling flexibility overall for parking is good,” he said. “But for adaptive reuse, it's absolutely crucial.”