Architects use their design skills to reach their goals for their multifamily clients, helping find solutions that save money, offer better amenities, boost resident well-being or mitigate tricky sites.

They say that collaboration is key in the architect-developer relationship.

The more architects learn from various stakeholders before design begins, the better they can meet client needs, site or code constraints and community desires, while avoiding costly changes down the road.

“The most successful projects involve clients who trust our process,” said Benjamin Kasdan, principal at the Tysons, Virginia office of KTGY. “They have a vision, but don’t get caught up in trying to solve specific problems, because they are confident enough to relinquish some control.”

David Haresign, partner of Washington, D.C.-based Bonstra|Haresign Architects, encourages development partners to consult his team before setting a budget because architects can often spot potential site constraints before they become costly design changes. Managing partner Bill Bonstra also makes sure clients understand the location’s hot buttons — things like traffic, noise, historic preservation, political concerns — especially in urban areas.

Kate Conley, a partner at San Jose, California-based Architects FORA, advises developers to invite community involvement from the beginning to learn their issues and possibly avoid roadblocks later in the project.

“We’ve been pushing hard for this approach because it brings advocacy voices to the table,” Conley said. “We all get a richer body of input and a greater sense of assurance that this specific project is a fit for this neighborhood context rather than us helicoptering in and deciding what’s right.”

Value creativity

A well-designed apartment offers more than aesthetic benefits, Conley said.

She sees a political advantage to creating a visually appealing building that makes neighbors and city officials happy. She primarily works on affordable housing projects, which “often have a hill to climb to be accepted by the community,” so a building’s appearance gives developers an advantage.

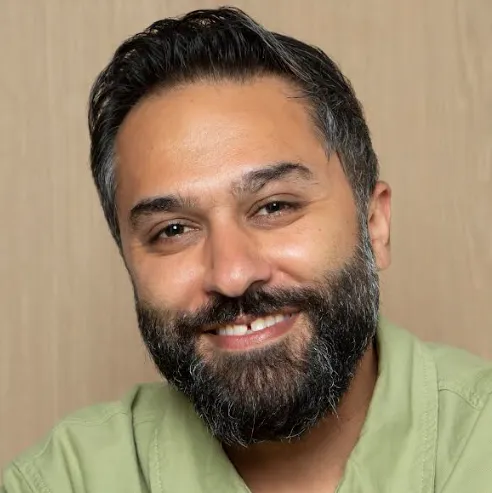

Plus, not all aesthetic elements cost more, according to Pedram Farashbandi, a principal at San Francisco-based David Baker Architects.

“We are not adding features simply to enhance the design,” he said. “We justify them by how they improve the quality of spaces and overall perception of the building. For instance, whether a courtyard is fully enclosed or open to a public way, the costs remain the same. However, the quality of the courtyard greatly improves when it is open on one side, also enhancing the building's exterior aesthetics.”

Creativity and beauty might not always cost more, but the earlier developers embrace an architect’s value the better their chances for higher savings and less risk, Kasdan said.

“Developers have a set of goals and we as architects can generate different ways to accomplish those goals,” he said. “And the earlier we’re involved, the more we can test these ideas and recommend which strategy works best. This process can even help our clients discover their true priorities.”

Another advantage to early collaboration is winning a commission. Conley often designs projects for clients to submit against other affordable housing developers. Understanding this dynamic can inform their design to make it more competitive.

“For example, the cost per unit might be the tiebreaker,” she said, “so how can we address this aspect in a durable, functionable, and beautiful way—especially in the Bay Area where things are more expensive.”

Haresign wants to make it clear, however, that architects aren’t cost estimators. They understand budget realities and judicious design decisions, but their jobs are “to add value by making a better project for our clients,” he said.

He also warns multifamily developers against trying to cut costs — sometimes known as value-engineering — after the design phase. The time it takes to figure out how to make the reductions, redraw the plans and rebid the construction can cost as much as the cuts saved.

For a project Haresign designed in 2007, the client “value engineered” three times, delaying construction for eight months. Construction costs rose around 30% during the delay, so the client didn’t save much but ended up with a cheaper building.

“We ended up finishing just before the depressed market hit,” Haresign said, “as opposed to the hot market we had just a few months before, so units also took longer to sell.”

More for the money

Architects can also increase a multifamily community’s market appeal, a building’s longevity and residents’ wellbeing without adding to costs. Sustainable materials, for example, are often the most durable, saving the developer on building maintenance over time. And durable materials can boost a building’s resilience, another money-saving feature for clients and one benefitting residents.

“We also have to think about how people can live in our buildings without power,” said Conley, “or stay comfortable with windows shut because of wildfire smoke. These projects are safe harbors, not just homes.”

In addition to environmental impact studies, many research firms now also provide white papers on design characteristics best-fitting certain groups. Conley seeks out and shares this research to give developers “data-driven reasoning behind why we suggest certain design features for, say, trauma-informed design or aging in place.”

Many smart design features, such as solar orientation or the location of outdoor spaces, don’t add to costs, according to Kasdan.

Some design choices might cost a little more, but Farashbandi cautions developers not to underestimate their importance.

“For instance, corridors and stairs tend to be minimized in size,” he said. “It’s not only a matter of size, but also quality of light and finishes, access to views, and various other factors. People spend a considerable amount of time in these circulation spaces, they have an impact on the overall ambiance of the community.”